Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Interesting Study on Elk and Beetle Kill Avoidance

- Thread starter 406LIFE

- Start date

2rocky

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jul 23, 2010

- Messages

- 4,968

Beetle killed trees would still prevent light from getting to the understory more so than a burn since they would still have some needles on the branches. I'd be interested to compare biomass of forage in beetle killed vs burned vs logged.

COEngineer

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jul 6, 2016

- Messages

- 1,463

Completely anecdotal, but I saw some of the best forage I have ever seen on public land a few years ago while helping RMEF with a fence removal project. It was a beetle kill area where the trees had been dead about 3 years IIRC and so the needles had all fallen off. I was just amazed how thick and lush the understory was. Maybe the linked study was done before the needles fell off? Or maybe elk avoid areas with trees falling all the time?

BrentD

Well-known member

Not having read it, was this in wolf country?

LuketheDog

Well-known member

Odd, I see elk in beetle kill quite a bit...

Last edited:

BigHornRam

Well-known member

Any results on this Elkhorn beetle kill study yet?

https://missoulian.com/news/state-a...cle_324ea078-e145-574e-9b45-213f6d60e693.html

https://missoulian.com/news/state-a...cle_324ea078-e145-574e-9b45-213f6d60e693.html

BigHornRam

Well-known member

Not having read it, was this in wolf country?

S E Wyoming. Have wolves showed up there now? Hadn't heard that they have.

huntin24/7

Well-known member

I read that earlier this morning. Just curious from guys more in the know, with the prevalence of beetle kill that's going to keep increasing and the increase I forrest fires sure to follow, how do you guys see that changing the dynamic of different species like elk and mule deer over time, like say 10-20 years from now?

Any results on this Elkhorn beetle kill study yet?

https://missoulian.com/news/state-a...cle_324ea078-e145-574e-9b45-213f6d60e693.html

Here you go.

http://fwp.mt.gov/fishAndWildlife/diseasesAndResearch/research/elk/elkhorn/default.html

BrentD

Well-known member

Interesting how little bulls and cows differ in their distributions from each other and over time. Really very little change is apparent through the bulk of the year and the whole hunting season.

Nameless Range

Well-known member

I recently made some maps regarding this very subject, but I can no longer attach images so I will reference this web map created by the USFS Forest Health Team. It's from 2012. Click on the 2012 National Insect and Disease Risk Map layer to expand the sub layers.

https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?layers=2022e3f664894959bddb6cb73eafb24b

I don't think folks realize the absolute scale of what the beetles did 10 years ago. The scope is incredible when you walk upon it. In the area southwest of Helena where I live and wander, there are chunks of forest tens of thousands of acres in size with greater than 50% tree cover loss, much of which is closer to 90%. And these are contiguous chunks. It really is incredible along the continental divide south of Helena. Once those trees began to fall in their majority, certain chunks of ground are functionally impenetrable. Taking a wrong path in that stuff with a few miles to go to the truck can be humbling - like an a$$ whooping.

I think the observations in this study will become even more prescient as time progresses. Half the lodgepole that succumbed to the beetles a decade ago is still standing. In the first few years following the die-off most still stood, and so you could still walk and hunt in it. In the last few years, and following a large windstorm in 2017, in the Boulder Mountains anyway there are numerous chunks of public ground, many square miles in size, that are impassible to both man and elk. Of course there are paths and areas thin enough to provide as corridors for movement, but there are massive chunks of ground where nothing but squirrels, rabbits, and bobcats wander. One need only suffer their way into 10 square miles of this blowdown mess, weeks after a snow, to realize there are no ungulate tracks and mountains that once held elk are now devoid of them.

I would be curious to see how elk use the beetle kill during hunting season, when those focused areas that provide easy living are hammered by people. I have a hunch that elk have very specific places they go in the beetle kill for sanctuary, but most of it is no good to them. What the area I like to play in needs is a cleansing fire, about 300,000 acres in size. Rereading what I just wrote, I'm aware I may be looking at it from the perspective of a hunter and not from a "whole-ecosystem" standpoint. I often find myself in awe of the beetle-kill.

https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?layers=2022e3f664894959bddb6cb73eafb24b

I don't think folks realize the absolute scale of what the beetles did 10 years ago. The scope is incredible when you walk upon it. In the area southwest of Helena where I live and wander, there are chunks of forest tens of thousands of acres in size with greater than 50% tree cover loss, much of which is closer to 90%. And these are contiguous chunks. It really is incredible along the continental divide south of Helena. Once those trees began to fall in their majority, certain chunks of ground are functionally impenetrable. Taking a wrong path in that stuff with a few miles to go to the truck can be humbling - like an a$$ whooping.

I think the observations in this study will become even more prescient as time progresses. Half the lodgepole that succumbed to the beetles a decade ago is still standing. In the first few years following the die-off most still stood, and so you could still walk and hunt in it. In the last few years, and following a large windstorm in 2017, in the Boulder Mountains anyway there are numerous chunks of public ground, many square miles in size, that are impassible to both man and elk. Of course there are paths and areas thin enough to provide as corridors for movement, but there are massive chunks of ground where nothing but squirrels, rabbits, and bobcats wander. One need only suffer their way into 10 square miles of this blowdown mess, weeks after a snow, to realize there are no ungulate tracks and mountains that once held elk are now devoid of them.

I would be curious to see how elk use the beetle kill during hunting season, when those focused areas that provide easy living are hammered by people. I have a hunch that elk have very specific places they go in the beetle kill for sanctuary, but most of it is no good to them. What the area I like to play in needs is a cleansing fire, about 300,000 acres in size. Rereading what I just wrote, I'm aware I may be looking at it from the perspective of a hunter and not from a "whole-ecosystem" standpoint. I often find myself in awe of the beetle-kill.

Last edited:

COEngineer

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jul 6, 2016

- Messages

- 1,463

impassible to both man and elk.

In my experience, the impassable to man state happens before the impassable to elk state. Before the snow gets deep, there are areas where I have followed elk tracks into deadfall that wore me down to the point of thinking, "Man, if I killed something in here, I would have to eat it on-site because I would never be able to pack it out." So, I am sure the deadfall reduces how much the elk use those areas, especially outside of hunting season, but I also think there is probably a lot more security habitat, at least secure from human hunters (and if I'm not mistaken, wolves don't like the thick stuff either, although we don't have many of those in CO yet).

ImBillT

Well-known member

- Joined

- Oct 29, 2018

- Messages

- 3,821

Once the termite population catches up to the food supply it won’t take all that many years to take care of all that blow down, and then you’ll see lush green food sources like you never imagined. Those trees have evening minerals and micro nutrients from deep down in the soil beyond the reach of the roots of smaller plants for decades and now they’re all on the surface and in a bioavailable form. Between the enhanced nutrition and the all the CO2 the termites and microbes will be releasing from digesting that wood the food sources will be incredible.

A fire wouldn’t be the worst thing. It would be faster.

A fire wouldn’t be the worst thing. It would be faster.

Last edited:

D

Deleted member 20812

Guest

Odd, I see elk in beetle kill quite a bit...

My experience as well. I’m guessing the size and scope of the kill area plays a big role in whether they use it or not n

BigHornRam

Well-known member

Dry cold sites like the mountain west where lodgepole pine thrive, dead downed timber can take hundreds of years to decompose. Fires, if not too intense are the best way to release the dead trees nutrients into the soil. Woody biomass however has little reletive nutrient value. Nitrogen is the most important nutrient necessary to produce lush green growth. Nitrogen fixing plants like alder, lupine and ceanothus that take over after a fire, do a lot to increase the nitrogen levels in the soil.

2rocky

Well-known member

- Joined

- Jul 23, 2010

- Messages

- 4,968

Dry cold sites like the mountain west where lodgepole pine thrive, dead downed timber can take hundreds of years to decompose. Fires, if not too intense are the best way to release the dead trees nutrients into the soil. Woody biomass however has little reletive nutrient value. Nitrogen is the most important nutrient necessary to produce lush green growth. Nitrogen fixing plants like alder, lupine and ceanothus that take over after a fire, do a lot to increase the nitrogen levels in the soil.

This is true. But soil organic matter is necessary for good grass and forb growth.

Wood ash is High in Potassium and i think that helps as well in getting grass growth. It is equivalent to 0-1-3 (N-P-K) fertilizer. Combine that with Carbon from forest duff over the years on a North facing damp slope and you have pasture quality grass the next spring season.

I think as a restoration project, felling and burning blocks of beetle kill is worthwhile. Controlling the spread of the fire is difficult though..

TrickyTross

Active member

I recently made some maps regarding this very subject, but I can no longer attach images so I will reference this web map created by the USFS Forest Health Team. It's from 2012. Click on the 2012 National Insect and Disease Risk Map layer to expand the sub layers.

https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?layers=2022e3f664894959bddb6cb73eafb24b

I don't think folks realize the absolute scale of what the beetles did 10 years ago. The scope is incredible when you walk upon it. In the area southwest of Helena where I live and wander, there are chunks of forest tens of thousands of acres in size with greater than 50% tree cover loss, much of which is closer to 90%. And these are contiguous chunks. It really is incredible along the continental divide south of Helena. Once those trees began to fall in their majority, certain chunks of ground are functionally impenetrable. Taking a wrong path in that stuff with a few miles to go to the truck can be humbling - like an a$$ whooping.

I think the observations in this study will become even more prescient as time progresses. Half the lodgepole that succumbed to the beetles a decade ago is still standing. In the first few years following the die-off most still stood, and so you could still walk and hunt in it. In the last few years, and following a large windstorm in 2017, in the Boulder Mountains anyway there are numerous chunks of public ground, many square miles in size, that are impassible to both man and elk. Of course there are paths and areas thin enough to provide as corridors for movement, but there are massive chunks of ground where nothing but squirrels, rabbits, and bobcats wander. One need only suffer their way into 10 square miles of this blowdown mess, weeks after a snow, to realize there are no ungulate tracks and mountains that once held elk are now devoid of them.

I would be curious to see how elk use the beetle kill during hunting season, when those focused areas that provide easy living are hammered by people. I have a hunch that elk have very specific places they go in the beetle kill for sanctuary, but most of it is no good to them. What the area I like to play in needs is a cleansing fire, about 300,000 acres in size. Rereading what I just wrote, I'm aware I may be looking at it from the perspective of a hunter and not from a "whole-ecosystem" standpoint. I often find myself in awe of the beetle-kill.

Great stuff and thanks for sharing!

I recently made some maps regarding this very subject, but I can no longer attach images so I will reference this web map created by the USFS Forest Health Team. It's from 2012. Click on the 2012 National Insect and Disease Risk Map layer to expand the sub layers.

https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?layers=2022e3f664894959bddb6cb73eafb24b

I don't think folks realize the absolute scale of what the beetles did 10 years ago. The scope is incredible when you walk upon it. In the area southwest of Helena where I live and wander, there are chunks of forest tens of thousands of acres in size with greater than 50% tree cover loss, much of which is closer to 90%. And these are contiguous chunks. It really is incredible along the continental divide south of Helena. Once those trees began to fall in their majority, certain chunks of ground are functionally impenetrable. Taking a wrong path in that stuff with a few miles to go to the truck can be humbling - like an a$$ whooping.

I think the observations in this study will become even more prescient as time progresses. Half the lodgepole that succumbed to the beetles a decade ago is still standing. In the first few years following the die-off most still stood, and so you could still walk and hunt in it. In the last few years, and following a large windstorm in 2017, in the Boulder Mountains anyway there are numerous chunks of public ground, many square miles in size, that are impassible to both man and elk. Of course there are paths and areas thin enough to provide as corridors for movement, but there are massive chunks of ground where nothing but squirrels, rabbits, and bobcats wander. One need only suffer their way into 10 square miles of this blowdown mess, weeks after a snow, to realize there are no ungulate tracks and mountains that once held elk are now devoid of them.

I would be curious to see how elk use the beetle kill during hunting season, when those focused areas that provide easy living are hammered by people. I have a hunch that elk have very specific places they go in the beetle kill for sanctuary, but most of it is no good to them. What the area I like to play in needs is a cleansing fire, about 300,000 acres in size. Rereading what I just wrote, I'm aware I may be looking at it from the perspective of a hunter and not from a "whole-ecosystem" standpoint. I often find myself in awe of the beetle-kill.

Thanks for this—I too wander/stumble through this same stuff outside of Helena. You are absolutely right—the change over the past decade is something else. The other component I could really do without is dodging those trees when they decide to fall. Can’t tell you how many times that’s happened in recent years—even on relatively calm days.

Nameless Range

Well-known member

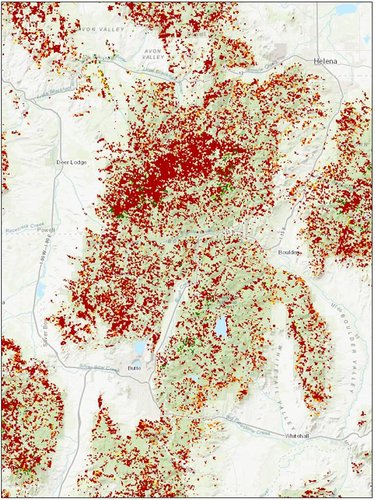

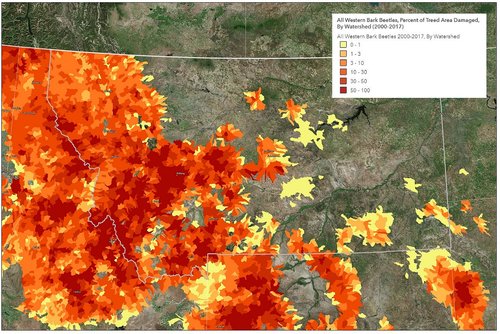

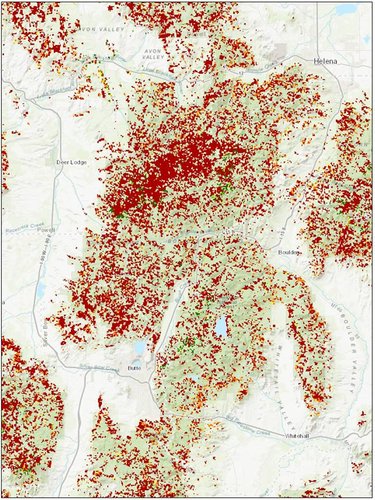

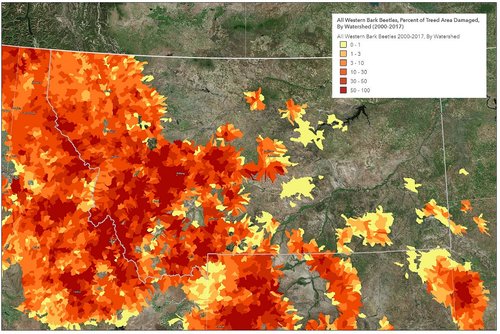

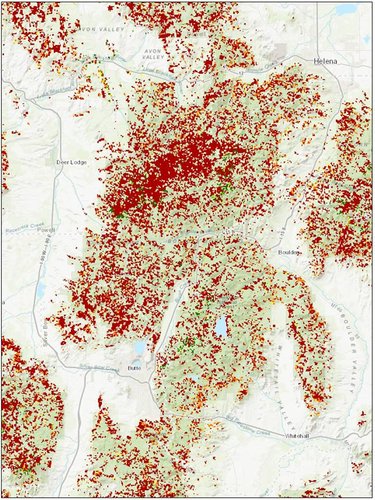

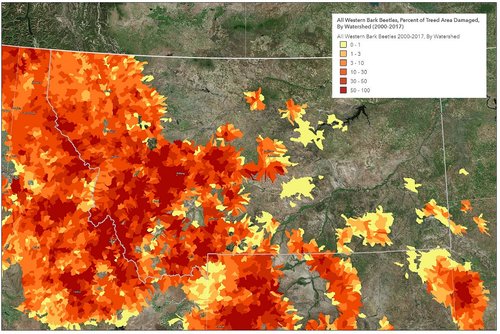

Now that I can upload images, here's a couple maps I wanted to share at the time of this thread.

First shows the Basal Area Lost in the Boulder Mountains, south of Helena. The red pixels are areas with greater than 30% basal area loss. Essentially meaning that over a third of the trees within those areas are dead, and in much of those pixels it is closer to 100%.

The second shows the percentage of trees damaged by beetle-kill in Montana, delineated by watershed.

First shows the Basal Area Lost in the Boulder Mountains, south of Helena. The red pixels are areas with greater than 30% basal area loss. Essentially meaning that over a third of the trees within those areas are dead, and in much of those pixels it is closer to 100%.

The second shows the percentage of trees damaged by beetle-kill in Montana, delineated by watershed.

Attachments

Similar threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 693